In this think piece, Michael Waites, teacher/ASC lead at Catcote Academy and SSAT Leadership Legacy Fellow, shares a student’s journey following his diagnosis with autism spectrum disorder

Glossary of Terms

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) – I use this term when describing a diagnosis of the neurological condition autism. In my setting, we prefer the term Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) as this reflects the social model of disability rather than the medical model and is host to less negative connotations.

Neurodiverse – When I use this term I am referring to those who see the world in a different way whether that is due to being autistic or another neurological difference.

Neurotypical – When I use this term I am referring to people who are not displaying or are not characterised by being autistic or any other neurological atypical patterns of thought or behaviour.

Preverbal – This is a term I use to describe a learner who has not yet used spoken language to communicate.

SEND – Special Educational Needs and Disabilities.

Preface

I wish I could say that this story of an autistic young man navigating secondary school was down to my actions as a teacher and autism lead, but it wasn’t. I played my part and tried my best but ultimately tragedy became the biggest factor. That is why this story is important.

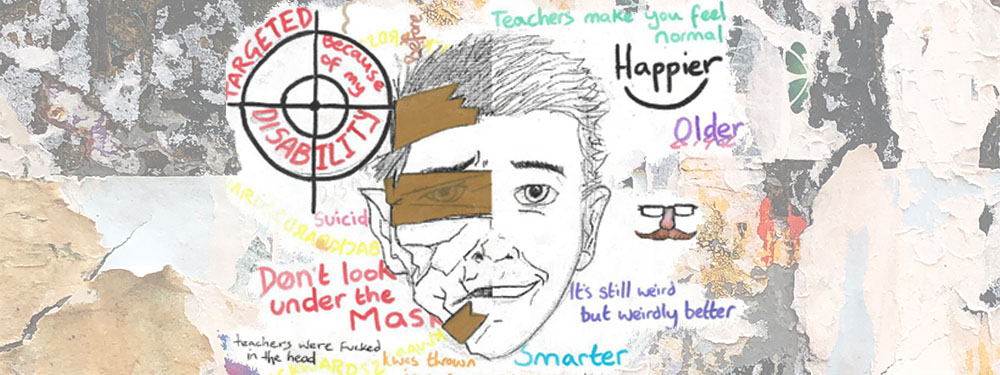

When I met Will, he didn’t have a voice. By that I don’t mean he was preverbal, he is very articulate, but he had given up on using his voice for anything other than talking about his interests with a couple of adults he didn’t hate or shouting at those he did. Since then he has found his voice, and it is profound. Therefore, much of what you will read and see in this article has come from Will. From chapter titles to imagery to direct quotes, that is all him and I couldn’t be prouder.

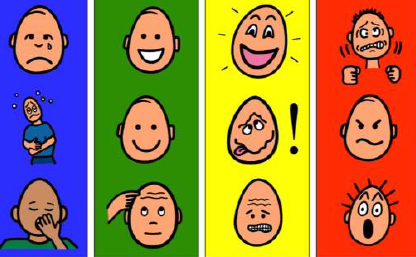

Something that Will found virtually impossible when we met was sharing how he was feeling. The first strategy I introduced him to was the zones of regulation and (although for years he told me he hated them) he has decided that they should be used to let the reader know how he was feeling at each part of his story (I am delighted!). In a nutshell, the zones of regulation categorise all the different ways we feel into four concrete-coloured zones. The blue zone represents ‘low feelings’, the green is where ‘calm feelings’ belong, yellow represents ‘feeling heightened but in control’ and red zone is ‘feeling heightened and out of control’. It is highly visual and the zones tend to be presented as equal blocks of colour from blue to red.

As Will views the world through a unique lens, when he was able to, he explained that he saw them like ever-shifting dials depending on how he felt. Sometimes his blue zone might be very wide indicating he was depressed, at other times his red zone might be notably short, indicating that he felt regulated and unlikely to lose control. This is how he would like to demonstrate his feeling at each stage of his journey.

Chapter 1 – Choosing between two evils*

Will’s story begins in his final year at primary school. He hadn’t received an autism diagnosis but his school were aware of his differences and difficulties. They advocated for a secondary school with an attached SEND provision that was described as a ‘sanctuary’ for those with additional needs. Will had to say goodbye to many of his primary school friends who all went to a different local secondary school.

“In Year 7 school was just school, I wasn’t happy or sad. It was mixed emotions with quite a bit of anxiety because I was the only kid to go there. My new school leant towards the stricter side but kids were treat fairly. Rewards and discipline seemed logical. I always liked science and the science teacher could dislocate her elbow in a weird way, so that was a fond memory.”

* “I say two evils because I now know that the school my primary mates went to is just as bad!”

Chapter 2 – A rapid decline

Year 8 brought with it change. Will received a diagnosis of ‘autism spectrum disorder’ (ASD) and, more significantly, his school became part of a multi-academy trust. With it came a new behaviour policy that meant supporting adults were expected to give a series of consequences (C’s) for disruptive behaviour and exclusions for significant incidents or continued disruption. For Will this felt like the understanding and leniency he had experienced from adults he trusted had gone.

“You know on superhero movies when there is a supervillain organisation with a catchy 3-letter name? People think they are good and here to help, when really, they do the opposite. That was the academy. They took any accusation as proof, no trial, no jury, just C’s.”

I can appreciate Will’s sentiment; his school experience had changed significantly:

- Suddenly when his sensory system couldn’t tolerate the feeling of his shirt on his neck and he loosened it = C (improper uniform).

- Suddenly when he was unable to predict what each adult considered was an inappropriate question in a lesson = C (being disrespectful).

- Suddenly when his naturally poor executive functioning meant he forgot his planner or pencil case = C (missing equipment).

- Suddenly when he was focusing on a fine detail rather than seeing the bigger picture that the teacher was trying to teach him about = C (disengaging from learning).

- Suddenly when a teacher provided some learning he really enjoyed and he wanted to focus on it for longer than the 3 minutes laid out in the lesson plan starter = C (ignoring instructions).

What’s worse is the ‘sanctuary’ for those with additional needs was now combined with isolation for students that had accrued too many C’s to be in lessons, but not enough to be excluded. The cherry on the cake was that under the new academy trust, supporting adults that were previously deployed for SEND students, were now asked to stay in a lesson to support the teacher even if their SEND student needed to go to the (was) ‘sanctuary’.

Chapter 3 – Uncertain future

Feeling alone, and often sat alone in what was once a ‘sanctuary’, school life had become hell for Will. He had always found eating at school difficult but now he had stopped completely. He couldn’t be around any peers because of his outbursts. He spent much of his time in a room the school had provided for him, accessing no learning and having regular violent incidents.

“How I felt in [school] was unbearable, I was having panic attacks from just saying the word never mind actually being in the place itself”

By the time the academy contacted my setting to seek support, Will was on a reduced timetable in all senses of the words. He was expected to be in school for half of a full timetable but was typically only managing until 10am when he was excluded due to “refusal to work”.

My memory of Will back then was like a ticking time-bomb. We could chat about Dragon Ball Z and he would share his often-morbid sense of humour. He tolerated me going on about autism and the zones but I always felt that if I had pushed the wrong button there could be a dangerous explosion. Luckily defusing internal bombs, especially in autistic children, is my speciality so we hit it off. I won’t give an exhaustive list but the fundamental barriers for Will were clear to me, everyone was reacting to what he was doing but nobody was considering why he was doing it. Add to that isolation when you need support the most, and you have a recipe for an explosion.

An email I sent at the time reads:

What I was hoping to be able to do was to supply [a supporting adult] with a system of strategies to support Will to manage school and work towards greater independence and engagement in learning. However, that part of what I can offer will be difficult if there isn’t a supporting adult in the [SEND provision/sanctuary] to support Will.

And so begun a frustrating period for everyone. Will was doing his part, engaging more and more with me each week. His attendance in school was increasing but he was continuing to have some explosive incidents. His school, however, felt that all of my recommendations went way beyond ‘reasonable adjustments’ and were not in line with their behaviour policy. Faced with unreasonable reasonable adjustments what could I do to help Will?

So, I invited him to visit my setting one afternoon a week so he could interact with like-minded peers and hopefully have some positive experiences. He loved it and so did his mum.

I then took my frustration to the local education authority (LEA) and explained that Will wasn’t accessing any learning at school and has shown that he is happier and less anxious in my setting. The resounding response, “he doesn’t meet the criteria”, referring to a lack of significant learning difficulty. Will had fallen into the dreaded “too clever” limbo.

Too clever limbo (ʌnˈdʒʌst) noun. 1. The place between a mainstream education setting that is not able to meet a child’s needs and a special education setting that can meet a child’s needs but they can’t attend; I can’t be happy or reach my potential because I am in the too clever limbo at the moment.

Will and his family were informed that he could continue to visit, but it wasn’t a long-term option.

Chapter 4 – Staring into the void

“It’s weird because I was feeling so low and depressed that I couldn’t think straight, unless I was thinking about hurting myself, then I could focus. I was scared for my own life. At school, I was allowed to use a laptop and I had searched for ways to do it and I had searched for how to not feel like hurting myself, but they only focused on the first bit. They just took all the tech off me.”

Things continued to get worse for Will. Discovering he would never be given a chance to attend my setting meant he no longer saw the point of the visits. The last time I thought I might see him was after he threw a table at me and left with his mum.

Will continued to hate school and that’s when it happened… Will had found a way to lock the door of the room he used in school, barricaded it and tightened his tie around his neck as hard as he could.

Chapter 5 – A saving grace

Thankfully adults were able to break into the room before Will sustained any serious injuries. The incident had left everyone involved in his care understandably shaken. The LEA made the snap decision that my setting should establish an additionally resourced provision (ARP) and Will should be the first on roll. We began a phased transition with the aim that Will would be attending my setting full time at the beginning of Year 9.

“When I first joined I was OK to happy, but I now understand that I had next to no tolerance. We called it the thin yellow line. I jumped from something going slightly wrong straight to out of control.”

Will joined my class, but his traumatic experiences meant that it took several months for him to enter the classroom. That wasn’t a problem, there were lots of things we could do in the corridor just fine. Things only got tricky when we found out Will loved learning about the black death and particularly liked the gory images. We created a mobile project board that could be spun around to hide anything gory akin to that of Miss Honey’s classroom in Matilda.

Will was doing well despite everything he had gone through, but there were often hard times. Unlike his previous setting, Will was rarely explosive with us. In fact, he would freeze and shutdown as if he was having a fierce battle inside his mind, trying to contain the explosion so as not to spoil his relationships with us. After a few explosions, Will understood that what we cared about most when they happened was that he felt safe. Afterwards, despite the punches or the thrown resources, what we cared about most was that Will understood that no bridges were burned.

“This is a place where the teachers actually try to understand the students instead of just dismissing them, the staff here 9/10 times know what they are getting into and learn how the students react to certain things to know what helps them calm down quicker and what makes them more agitated”

Before the school year was out, Will had made it into the corner of the classroom. Still wearing his coat, not eating or drinking and only taking part in one-to-one activities linked to his favourite things. What he had developed was trust. He knew that we were constantly thinking about how he was feeling and what possible bumps in the road were coming up for him. We navigated those bumps together and by the time we broke up for summer, he was ready to move into a more appropriate class. Success!

Chapter 6 – A steady incline

Year 10 began and Will found himself in the corridor again, transitioning to a new classroom with a new teacher and peers is hard no matter how much transition work you do. Fortunately, his new teacher was open-minded and fully subscribed to my relationship-focused approach (it also helped that he had sound knowledge of the Nintendo universe). This time it didn’t take long before Will was in the classroom and now he was dipping his toes into group learning. Being the ultimate champion of “Super Smash Bros: Brawl” on the Nintendo Wii U gave him esteem and many of his classmates looked up to him.

Time passed without any explosions. Tricky times were managed well and Will accepted support to develop strategies to overcome them when they cropped up again. His coat came off and we watched proudly as he started to come to school with new trainers on or a new hoodie. Confidence was building, guards were dropping and friendships were being made. Then, one day, Will had a drink of coke and we all almost fainted.

It wasn’t long before my setting had two more ARP students on roll and we decided to establish an ARP class. Thankfully Will had lots in common with them and it didn’t take long before Will was being invited to his first birthday party since he was young.

Introducing the trio to ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ was when Will was able to really showcase his confidence, who would have thought that Will (Or should I say Spanish fish-man, Esteban Estebana) would be such a good adoptive father to thirty little goblins?!

This is when COVID-19’s impact on society cut the school year short due to a national lockdown.

Chapter 7 – True happiness

“Before the lockdown I was still feeling depressed. I wasn’t sharing those feelings at school because I was so grateful for everything they had done for me, I didn’t want to seem whiny. Lockdown provided the opportunity to reflect that I needed, a chance to clear my head. I did a lot of thinking (and a lot of playing APEX legends online with a friend I made at school). It’s ironic but while most people were struggling with their mental health, I was realising how good I had it now and that, for the first time in a very long time, I felt happy.”

Now Will is in Year 11, he is a valuable member of a class of 4 ARP students. He looks out for younger students and is very sensitive to their difficulties, often explaining to supporting adults why he thinks they might need some help. Will is accessing an online learning platform throughout the school week and is working towards maths and English accreditation. His curriculum continues to focus on emotional regulation and social communication. His and his friends’ shared interests are at the heart of their learning, they have expanded their Dungeons & Dragons club beyond their group via ‘Zoom’ and Will now has 5 different teachers (and he gets on with them all!)

Conclusion

Will’s journey to true happiness raises a number of critical questions. Why does it take a child hitting rock bottom to gain access to the support they need? What are special schools providing that mainstream schools are not able to? What can be done for those ‘too clever’ limbo learners that are suffering but can’t gain access to a setting that understands them?

I think the bigger picture here is a national, systematic problem. Special schools are not able to meet the emotional, social and functional educational needs of very complex children and provide subject-specific teaching and learning up to GCSE level as effectively as a mainstream setting. Conversely, mainstream settings are not able to meet the complex emotional, social and sensory needs of their neurodiverse or autistic learners but can deliver a curriculum to GCSE. Hence, a group of learners are being let down both in terms of wellbeing and what they can achieve in school.

In an ideal world, a child like Will could feel safe and nurtured in the same secondary school their friends go to. However, this would require a dramatic shift from a consequence-focused behaviour model to a relationship-focused behaviour model. Sadly, this is looking less and less likely as multi-academy trusts and secondary schools in general are adopting similar ‘C’ based approaches to behaviour. In addition, despite the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) reporting the importance of relationships when aiming to improve behaviour, the Department for Education’s recent guidance has an almost opposite stance. The serious lack of reference to relationships and building trust within the guidance and the prominence of ‘expectations’, ‘exclusions’ and ‘rules’ is encapsulated by the subtle semantic change from “rewards and sanctions” to “sanctions and rewards”. It often makes me wonder, where would we be if autism heroes like Einstein, Turing and Fossey had to endure British secondary education in 2020? Would they reach their potential despite their quirks and less social nature? Or would constantly being awarded C’s crush their spirit?

Schools would also require an investment into creating an inclusive ethos that values neurodiversity and provides training and resources to meet diverse needs effectively. Again, this looks unlikely to become the norm in school any time soon. The ideological notion of inclusion that is regularly considered in schools, is very different from feeling included when you ask autistic young people about their lived experiences. For true changes to occur, autistic young people need to be at the centre of change and of their educational choices. Unfortunately, many autistic young people who could affect these changes are too busy trying to survive school life.

Until then, I think there is a model that could bridge the ‘too clever’ limbo gap:

The image (above) shows the journey of many autistic young people through mainstream secondary school, in my experience. Over KS3 their wellbeing declines and in turn so does their academic achievement. Typically, around year 9, either due to school refusal, increasingly dangerous incidents in school or serious mental health concerns, they join a special needs setting. Wellbeing improves significantly, as does academic achievement, but they don’t quite meet their academic potential because of the recovery curriculum required followed by a curriculum designed for less cognitively-able learners.

This image shows the potential journey of a learner like Will if they began their secondary career in a special school and then had a phased transition into a secondary school. KS3 would focus on their emotional, social and sensory needs with managing the challenges of mainstream school in mind. Then in KS4, they would be more equipped to access subject-specific learning at pace. A few years ago, we had a student for whom the planets aligned and they completed this journey through school. They started in Y7 so anxious that they couldn’t swallow their own saliva. They began accessing one maths lesson per week at a mainstream school in Y8 and gradually added more lessons, science and finally ICT. In year 11 they spent more time in mainstream than special and came out with excellent GCSE grades. Now he is accessing a higher education video game design and computer sciences course. The logistics were not easy, but it can be done.

So, how has all of this influenced my practice as a special educator and future leader? This experience has taught me to be a leader that fiercely defends the rights of young people with autism. I will endeavour to raise the profile of autism and neurodiversity across my community, shining a light on autism heroes and highlighting the challenges autistic people face that just don’t mesh with what is becoming the standard ‘school rules’. I will promote the development of ARP provisions and continue to save students like Will who are suffering every day in school. I will continue to shout about the ‘too clever limbo’ that plagues a community of young people with great potential and value, but who are currently unable to raise their voices.

Bibliography

A School Without Sanctions – Steven Baker & Mick Simpson (2020)

Behaviour and attendance checklist – Department for Education (2020)

Behaviour is about relationships. The DfE ignores this – Mary Meredith (2020)

Different Like Me: My book of autism heroes – Jennifer Elder (2006)

Improving behaviour in schools – Education Endowment Foundation (2020)

Mainstream is not for all: the educational experiences of autistic young people – Craig Goodall (2018)

Six tips for improving behaviour in school – Dave Speck – (2020)

The Reason I Jump – Naoki Higashida (2016)

The zones of regulation – Leah Kuypers (2011)

Uniquely Human – Barry Prizant & Tom Fields-Meyer (2016)

Why our school has no sanctions or punishments – Steven Baker & Mick Simpson (2020)