This article is the third in a series written by Mark Roberts, Head of English at Tavistock College. It was originally posted on his own blog.

This article is the third in a series written by Mark Roberts, Head of English at Tavistock College. It was originally posted on his own blog.

In this blog series I started out with a few general principles for comparing texts. Then I moved on to comparing unseen texts in a GCSE language exam. This final (I think) blog on comparison will put forward my preferred method for teaching links between literature texts with some examples, and will also look at how to make sophisticated comparisons.

Firstly, a reminder that pupils who turn up with the intention of winging it by finding comparisons on the day rarely do well. As an examiner you can just tell when they are grabbing at straws and making increasingly tenuous links between the texts.

Bear in mind again that the most effective way to compare – in my experience – is to analyse the key quotes that you fancy and then link the respective effects on the reader (or themes or feelings, which is often the same thing). So it makes perfect sense to plan these comparisons out and, crucially, practise these repeatedly in advance. To see if they work. And if they don’t then ditch them and start again. This way, I pretty much guarantee you, pupils can compare anything with anything.

But don’t some poems naturally ‘go better’ with others though, I hear you say? To some extent yes. Yet going down the route of linking texts in an obvious way can often lead to predictable, formulaic responses that are less likely to attract higher band marks.

It also drastically cuts down the options if pupils are given a named poem (or two) that they dislike. My way means they can have a favourite poem “banked” that will go with the poem given, rather than the recommended poems that ‘link together nicely’.

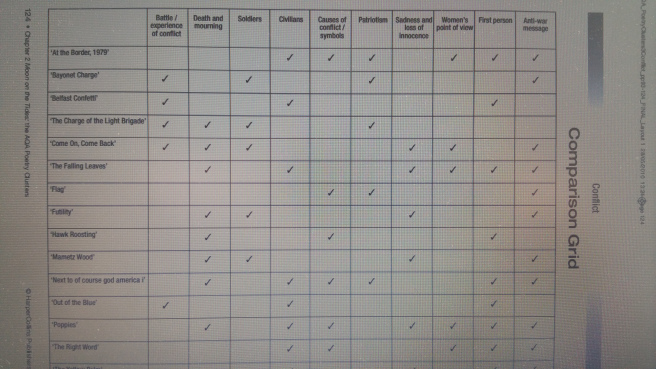

The revision guides tend to adopt this safety first approach, nudging candidates towards poems that snuggle up cosily with each other, like this example on the AQA poetry Conflict cluster (which I teach and mark as an external examiner):

And this is undoubtedly useful. Knowing which poems link on the theme of patriotism is helpful. Being able to say ‘Poem X is written in the first person, Poem Y is also written in the first person’ is significantly less helpful. I’ve always taught my pupils to use this kind of grid as a starting point and then move on to more interesting links. Such as:

1.

Perception: many poems – whether autobiographical or persona-driven – present the ideas and experiences through a particular lens, clear or distorted (or a combination of the two). The Conflict poems, for example, can all be linked through the effect of the ideas of perception – here are some example quotes:

Flag – ‘blind you conscience to the end’

OOTB – ‘are your eyes believing’

Mametz Wood – ‘a dance macabre’

The Yellow Palm – ‘a glass coffin’

The Right Word – ‘a boy who looks like your son, too’

ATB 1979 – ‘the autumn soil continued on the other side with the same colour’

Belfast Confetti – ‘it was raining exclamation marks’

Poppies – ‘sellotape bandaged’

Futility – ‘whispering of fields half-sown’

COTLB – ‘When can their glory fade?’

Bayonet Charge – ‘The patriotic tear that had brimmed in his eye’

The Falling Leaves – ‘like snowflakes wiping out the noon’

COCB – ‘the icy adorable lake’

ntocgai – ‘what could be more beautiful than these heroic happy dead’

Hawk Roosting – ‘my eye has permitted no change’

2.

Other fundamental themes that are central to the genre/category of text being studied. In conflict poetry, virtually everybody is going to write about loss of life and how war is generally a bad thing. Why can’t we give pupils a more challenging, interesting but clearly understandable way of looking at the texts? Another example:

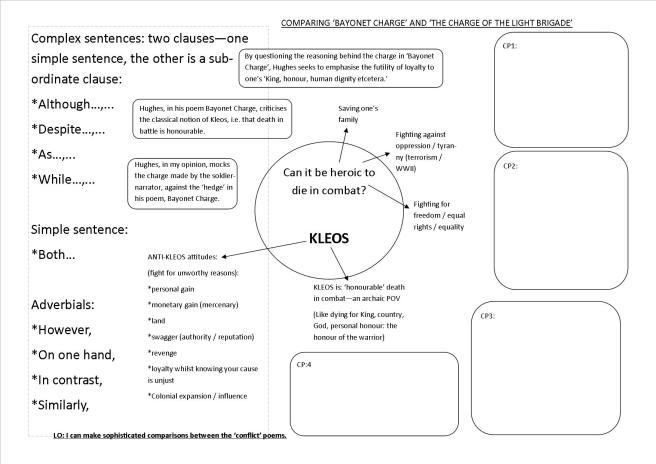

How do the Conflict poems support or challenge the concept of Kleos?

Kleos (Greek: κλέος) is the Greek word often translated to “renown”, or “glory”. It is related to the word “to hear” and carries the implied meaning of “what others hear about you”. A Greek hero earns kleos through accomplishing great deeds, often through his own death.

Here’s an extract from The Iliad that nicely sums up the level of personal sacrifice that leads to Kleos:

“My mother Thetis tells me that there are two ways in which I may meet my end. If I stay here and fight, I will not return alive but my name will live for ever (kleos): whereas if I go home my name will die, but it will be long ere death shall take me.” –Achilles

A developed investigation of Kleos might be attained through a resource like this:

For Relationship poetry the fundamental theme might be the notion of perpetual conflict between lovers/families. After all, relationship poems that merely espouse the beauty or perfection of one’s love or offspring are unremittingly dull. A typically clear-cut quotation from Oscar Wilde might provoke more interesting comparisons than the normal links on whether the love is requited or not:

‘Between men and women there is no friendship possible. There is passion, enmity, worship, love, but no friendship.’

By now some of you may be thinking that this is all well and good for top sets but surely beyond the realm of lower ability pupils. To begin with possibly, yet I would argue that with a little perseverence there is little difference in talking about themes of patriotism (love of one’s country) and Kleos (willing to die an honorable death for one’s country).

So why bother you ask? Isn’t this just unnecessary fancy language? I think not. One reason is that it offers a more nuanced view into the idea of personal sacrifice (exploring the idea that celebrates the bravery of a soldier in a morally unjust war for example).

Another reason is that it allows us to contextualise the texts way beyond the scope of the literary heritage/contemporary selection we are given. In Relationships clusters we might achieve this in a similar way by linking the genre back to Ovid or Petrarch. In a genuinely reflective way, rather than weak name-dropping. Which leads me on to…

3.

Putting sophisticated context at the heart of comparisons.

This, I agree, is difficult for some pupils. Nonetheless, with plenty of practice, this skill can become an integral part of comparing lit texts, especially if pupils are going to be preparing ‘here’s one I made earlier’ essays.

Once pupils have planned out which quotes they are going to use and have identified the effects on the reader, they can be given some memorable quotes to form part of their comparison of effects. For example:

War quotes

‘To consider people in their relation to war is, almost inevitably, to think in categorical and binary terms – combatant and civilian, men and women, young and old, injured and healthy, prewar and postwar, enemy and friend.’ – Sarah Cole, ‘People in War’ Cambridge Companion to War Writing (2009)

‘… the distinguishing characteristic of absolute despair is silence.’ – Wendle Berry, ‘A Poem of Difficult Hope’ (1990)

‘Reporting on war is a profoundly disillusioning experience… the abnormal becomes routine… war zones distort reality. War consists of thousands of acts of individual cruelty.’ – Jeremy Bowen, On the Frontline (BBC Documentary 2012)

‘The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of a million is a statistic.’ – Joseph Stalin

Relationship quotes

‘Francis Meres recorded exuberantly in 1598 that ‘the sweete witty soule… lives in mellifluous and honey-tongued Shakespeare.’

‘The wayward nature of erotic desire is a major theme in Ovid’ – Amorous Rites: Elizabethan Erotic Verse, Sandra Clark (1994)

‘The repertoire of denouements [for stories about love] is fairly limited: marriage, splitsville, murder, and mutual annihilation.’ – Louis Menand, The New Yorker, (1997)

‘it’s a formula that the best writers deviate from, refresh, or subvert…by using language that makes universal emotions seem unique, or, at least, ne’er so well expressed.’ – Deborah Treisman, The New Yorker, (2014)

‘Simply to say “I love you” or “you’re beautiful” is not interesting. Remember William Carlos Williams’ advice about writing – there is no truth but in things.” – Andrew Motion, The Guardian (2015)

What would this look like in practice?

Duffy’s use of the gunslinger motif offers an original take on what Louis Menand called ‘the denouement… of mutual annihilation’. By contrast the speaker of Khalvati’s poem is less interested in damaging the object of their desire and is willing to embrace a one-sided self ‘annihilation’.

It is possible, of course, to be sophisticated in the use of context without the bother of having to remember a few more quotes from ‘other readers’. A Band 6 example below illustrates this:

It’s interesting to note that Owen’s savage indictment of the callousness – ‘move him into the sun’ – of the generals shares similarities with Tennyson’s more muted criticism – ‘someone had blunder’d’ – of the Light Brigade commanders.

Both despair at the ineptitude of the upper echelons yet they also leave the responsible ‘someone’ anonymous. Owen does this to create a sense of universal indifference, whilst Tennyson, in his role as Britain’s poet propagandist, does so out of a contrasting need for discretion.

However, choosing quotes that get to the universality of the theme of conflict or relationships (or character or place if you’re mad enough to subject pupils to those poems for an exam!) means that pupils might only need to memorise one especially juicy quote that will elevate really good comparisons to an even higher plane. The Band 6 effort from above would be even better with a bit of Kleos or ‘absolute despair is silence’.

Let’s not make comparison a mere tag on then. I know it’s a hard skill to master. Hopefully though, these last three blogs having given you a few ideas about how to make the skills explicit enough for pupils to make those vital links.

This is the third and final blog of Mark’s series on comparing texts. You can read the first blog here, and the second blog here.

Share this post with your followers on Twitter. Or with your friends on Facebook.

Read more pieces from our guest writers.

Tavistock College is part of the SSAT network. Find out more about membership here.