Sir Michael Wilshaw is not long off stage at the ASCL annual conference. In his speech, he reinforced the message that Ofsted does not have a preferred teaching style – indeed he said he would personally take issue with inspectors who ignore this guidance and try to tell teachers there is only one way to teach. And he assured delegates that inspection reform must be a ‘two-way street’ – that Ofsted need the wisdom and experience of the best practitioners, and likewise practitioners need to know the very best are inspecting them, without fear or favour. He also recognised that the inspection stakes are far higher than they’ve ever been.

This is a message that SSAT welcomes – but it is imperative that it transmits into tangible action. In the recent SSAT / Reform report, Plan A+ 2014: the unfinished revolution, 60% of academy principals indicated their belief that all schools should have the same freedoms as academies and free schools. 80% said they would recommend academy status. But the report also laid bare the fact that few academies are using their freedoms to the full. The climate of uncertainty and rapid change we are in is undoubtedly a factor in the reluctance of academy principals to use their freedoms to drive innovation and change, alongside a lack of faith in the current accountability system.

For this reason we also welcomed the publication earlier this week of Watching the Watchmen: The future of school inspections in England, because we encourage the development of a dialogue between all stakeholders and Ofsted on the shape that school inspection should take.

We don’t dispute that ‘It is right and proper to have an independent schools inspectorate’ – when we look at school systems around the world, it is clear to see that with greater autonomy for schools comes greater accountability. But from the experience of some of our members it is clear that our current system requires reform. We know that school leaders can feel marginalised and threatened by the inspection system, and that when the phone call comes in, everything stops: the focus is entirely on the inspection.

Schools that have been judged ‘outstanding’ are fearful of losing the status and the benefits that it brings. Schools near the floor target are worried that they will fail to achieve their examination targets and be placed in a category. Schools judged as good are sometimes frustrated to wait an extra two years for an inspection when they want the benefits of the outstanding badge. Unsurprisingly, some schools graded as 3 or 4 for overall effectiveness can be reluctant to innovate their teaching as they are focused on getting the basics right. The distorting focus of uncertainty and fear means innovation is suffering as a consequence.

Schools that have been judged ‘outstanding’ are fearful of losing the status and the benefits that it brings. Schools near the floor target are worried that they will fail to achieve their examination targets and be placed in a category. Schools judged as good are sometimes frustrated to wait an extra two years for an inspection when they want the benefits of the outstanding badge. Unsurprisingly, some schools graded as 3 or 4 for overall effectiveness can be reluctant to innovate their teaching as they are focused on getting the basics right. The distorting focus of uncertainty and fear means innovation is suffering as a consequence.

We welcome the recommendation that inspectors should have relevant phase and sector experience. It is vital that inspectors have the credibility, knowledge and skills to offer both challenge and support to schools. However, the skills of inspectors could well have been enhanced by working outside a single school environment and so caution should be exercised with any inflexibility regarding the necessity of having recent teaching experience.

The data training currently offered to inspectors should certainly be improved and made more rigorous, although any attempt to produce an accredited examination will need to learn from the experience of SIP accreditation where the integrity of the single online test was widely discredited. Anything which helps to make both the Ofsted experience for schools and the judgements which emerge more consistent is to be welcomed, providing that it does not become over-bureaucratic. The recommendation that a non-participating observing inspector/HMI should be at a sample of inspections would be of benefit both to the inspection teams concerned and would also help increase the confidence of schools in the process. Given the move away from national curriculum levels from September 2014, it is essential that clear criteria for what constitutes good and outstanding practice are shared with schools and followed consistently by inspectors. Although the current framework makes it clear that there is no preferred style of teaching, and that schools know best what works for their pupils, school leaders need to be able to trust this.

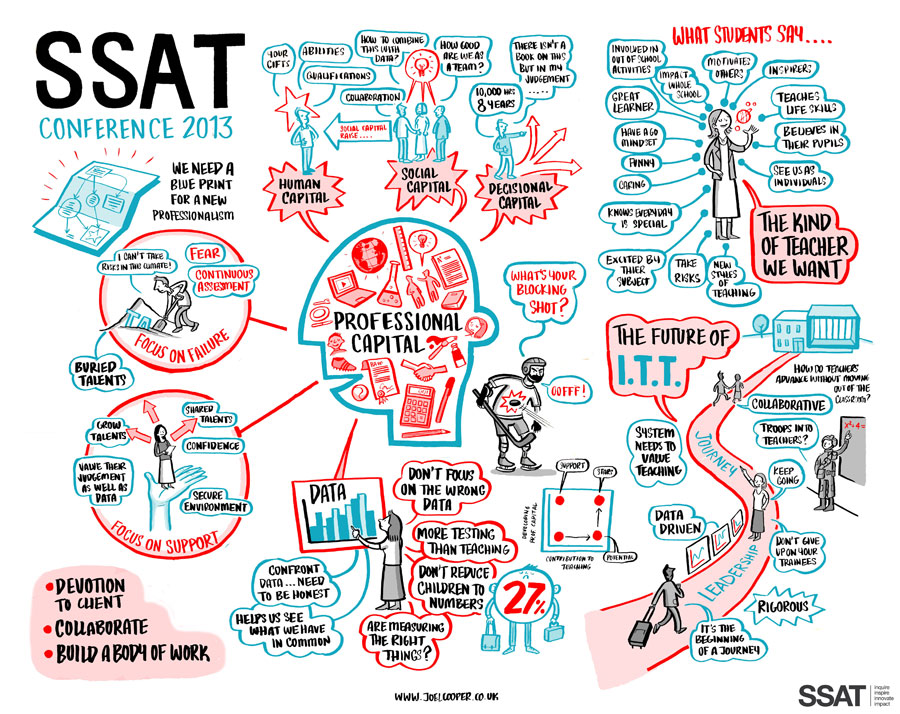

SSAT believes the current accountability system is resulting in a compliant profession. We support an independent inspectorate, as long as it does not skew what should be the constant focus of teachers and school leaders – ensuring their learners are experiencing effective teaching and learning. When we made intelligent accountability a key strand of our National Conference 2013, it was so that school leaders could examine how they interpret this term. One of the perspectives voiced was that if accountability forces schools to do things that go against a very well-grounded set of principles derived from research, evaluation and experience, then that accountability framework must be wrong. School leaders also advised each other to use and shape the framework to support their school development, and to tell their stories with confidence.

SSAT believes the current accountability system is resulting in a compliant profession. We support an independent inspectorate, as long as it does not skew what should be the constant focus of teachers and school leaders – ensuring their learners are experiencing effective teaching and learning. When we made intelligent accountability a key strand of our National Conference 2013, it was so that school leaders could examine how they interpret this term. One of the perspectives voiced was that if accountability forces schools to do things that go against a very well-grounded set of principles derived from research, evaluation and experience, then that accountability framework must be wrong. School leaders also advised each other to use and shape the framework to support their school development, and to tell their stories with confidence.

We hope that increased dialogue between stakeholders will generate more trust and lead to a fairer and better understood inspection system for schools – and that within such a climate, school leaders will feel empowered and supported to use their autonomy to deliver better outcomes for pupils.

SSAT, March 2014.